Laureate

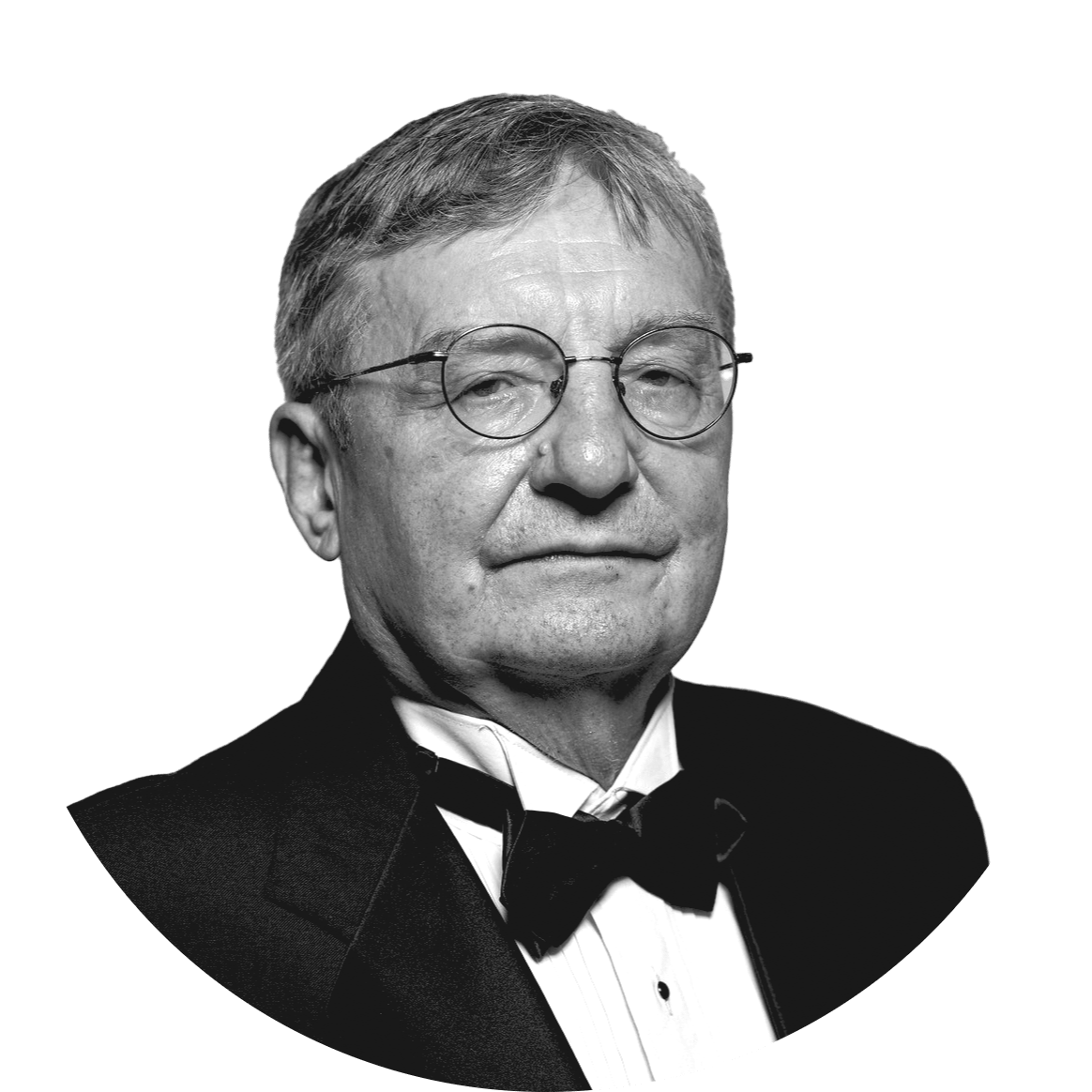

prof. MUDr. Josef Prchal, DrSc.

Laureate of the 2021 Neuron Prize for Lifelong Contribution to Science in the field of biology and medicine

For the contribution to the world of haematology and the description of the breakthrough phenomena usable in biomedicine

The world-famous haematologist, who helps his field as a scientist and doctor, described several breakthrough phenomena that can be used in biomedicine. Josef Prchal graduated from the Charles University and after the military invasion in 1968 went to the USA, but he maintained intensive relations with his homeland and continued to cooperate with Czech colleagues and students. Today he works in Utah. In his academic career, he created a comprehensive laboratory for research of red blood cell disorders. He has contributed to the field by describing the common origin of stem cells, discovering the molecular basis of Chuvash erythrocytosis (the first disease of the disrupted physiological response to oxygen deficiency) or, using the example of Tibetans, he identified genes responsible for human adaptation to high altitudes. Josef Prchal is a winner of the Stratton Prize, his research has been published by Science and Nature, and he is also considered as „a scientific father“ by two current Nobel Prize laureates.

The Secret of Blood

Unveiling the molecular basis of blood diseases and questioning established dogmas - this is the basic purpose of the scientific efforts of Josef Prchal, a globally recognized hematologist with Czech roots, who conducts an unusual duel: he combines science and medical practice.

At the American universities in Birmingham, Alabama, at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and now in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he currently works, he has built one of the world's most complex laboratories focused on the research of many red blood cell disorders. In addition, he is an external professor at the 1st Internal Medicine Clinic and the Institute of Pathological Physiology of the 1st Faculty of Medicine of the UK and VFN in Prague. He is the recipient of a number of awards, in particular the prestigious Henry Stratton Award, which he received from the American Society of Hematology in 2017 for lifetime contribution to the field – which he also considers his greatest achievement.

After his great teacher, Ernest Beutler, he took over the editorship of the important "Bible of Hematology" Williams Hematology, and his scientific publications (there are more than 400 of them) have over 26 thousand citations. He made his mark in world science mainly through his contribution to the discovery of the origin of blood elements from a common hematopoietic stem cell, the characterization and classification of congenital polycythemic conditions, and also the discovery of congenital mutations that affect the hypoxic signaling pathway.

While most scientists are focused on one thing, Josef Prchal has a wider scope thanks to his patients and is dedicated to whatever comes to his office. "I enjoy looking for the molecular basis of human disease, and blood cells are readily available," he says.

“When I want to examine you, maybe you'll give me blood, maybe not, but you'll definitely give me more than an eye or a heart. That's why we know the most about blood and red blood cells.”

Experiments with proteins

Už během studia na lékařské fakultě Karlovy univerzity pomáhal na biochemii jako takzvaný pomvěd neboli pomocný vědecký pracovník. V té době se zjistilo, že mutace konkrétních proteinů způsobují lidské nemoci a že například u černochů či Italů je častý deficit takzvané glukózo-6-fosfát dehydrogenázy, způsobující různé choroby od novorozenecké žloutenky po chudokrevnost. Psal se rok 1965 a Josefa Prchala to zaujalo natolik, že se rozhodl tento jev prozkoumat u černošských studentů, kteří studovali na pražských univerzitách. Spolu s ním se na tom podílel i pozdější známý onkolog docent Bohuslav Konopásek.

„Krev jsme od černošských studentů získali snadno, horší to bylo s chemikáliemi,“ vzpomíná profesor Prchal. Něco se jim podařilo sehnat, u zbytku improvizovali. Ze zabitého králíka získali isomerasu, z brambor kinasu, z glukosy připravili glukosa-6-fosfát. Vše smíchali s odebranou krví – a fungovalo to. Za tyto experimenty pak získali Purkyňovu cenu, která se ukázala jako zásadní pro další kariéru Josefa Prchala.

The way to the best laboratory

In 1968, after the Soviet occupation, he decided to emigrate. He fled to Canada via Hamburg with his fiancée at the time. They went by cargo ship because it was cheaper, but Josef Prchal had much less modest goals: he dreamed of reaching Ernest Beutler, who had discovered glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. "I was a young guy from the Czech Republic, not a Harvard student, my English was very broken. But the Purkinje Prize from Czechoslovakia made an impression and opened the way for me to the best laboratory."

He was in Denmark at the time of the occupation. Originally, he had planned to return home, serve out the war, and then enter academia. “When I heard about the entry of the troops, I was thinking whether to stay outside or return. I thought there would be a resistance at home, but that didn't happen.” So he decided to stay abroad. In retrospect, he considers the unplanned emigration and the necessity to communicate in another language to be the biggest obstacle he has overcome in his life. "My English isn't the best, but I probably knew a lot about molecular biology," he told himself. "It was clear to me that I had to make a living and take my work seriously. And so I tried to be good and I remembered enough under this stress."

He completed basic academic training in hematology at the University of Toronto, and after a year's internship with Professor Beutler in California, he returned to Canada to take up his first faculty position at McGill University in Montreal. But this career was prevented by a new law in the Canadian province of Quebec, which introduced mandatory knowledge of French. As Josef Prchal says: "The nationalists overdid it a bit and I ended up without a place without French." But Ernest Beutler helped and recommended him to the University of Alabama. "They offered me great conditions there and I could combine the clinic and science."

From the Dalajlama to Science magazine

Such a duel is, on the one hand, a joy, on the other hand, it is increasingly difficult to succeed in the pursuit of grants in science.

“You're always fighting the best in the field. And since most scientists spend their whole lives doing only one narrow field, they logically know it in the smallest details. I do a lot more, but not as detailed. Therefore, it is sometimes difficult to compete for grant money.

However, Josef Prchal made a significant contribution to world science with a number of unique findings. For example, he studied enzymes from red blood cells – the previously mentioned enzyme G6PD, which is located on the X chromosome. This study, in which Josef Prchal and his colleagues managed to describe that all blood cells arise from a common hematopoietic stem cell, was published in Nature in 1978 and received recognition. "We clarified the molecular nature of some other blood-born diseases," the professor explains the basic contribution of this work.

He devoted a large part of his research to the so-called polycythemia, a disease in which people have a lot of red blood cells. This phenomenon is often caused by a lack of oxygen. As part of his research, Josef Prchal was invited to Russia for a conference, where he learned about Chuvash polycythemia, about which there was no publication in English.

It was here that one of the most interesting stages of his professional career began, the research of the mentioned phenomenon in Tibet. “Surprisingly, most Tibetans do not have more red blood cells, even though they live five to six thousand meters above sea level, where there is really little oxygen. But some Tibetans do. That interested me and I wanted to find out what it was." Going to Tibet was not easy, the Chinese did not want to let the scientific team go to the Tibetans. "In the end, everything was successful thanks to the intercession of the Dalajlama, who testified that we are dealing purely with science, which he supported. The Tibetans then cooperated more and had their blood taken, which is particularly unpleasant for Buddhists. And we found evolutionary mutations that change the response to oxygen deprivation. We later published everything in Science and Nature Genetics," explains Josef Prchal.

Long-lasting excitement

He considers the most important for success to be prepared to take advantage of an opportunity, to ignore conventional thinking and to follow new approaches in science. "I was lucky to work with the best. Whenever I needed something, even on the weekend or in the evening, Professor Beutler and my other teacher Y.W. Kan, who discovered the mapping of the human genome by genetic polymorphism, was always happy to help. I am trying to repay them and pass this approach on," says the world-renowned hematologist. "I felt that I should give back to young people and students. Many of them were here after me, and then they set up their own laboratories."

By the way, just as Ernest Beutler fascinated Josef Prchal, it was Josef Prchal who inspired Ernest Beutler's son, the future Nobel Prize winner, for science. While still a high school student, Bruce spent a month in Prchal's lab. The flame of interest was ignited, and in 2011 Bruce Beutler, together with Jules A. Hoffmann, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery regarding the activation of innate immunity.

What would Josef Prchal advise students from his experience? First, have your own interests and opinions. Don't be afraid to disagree with professors and fight for your different opinions. And then also - to be aware of one thing: that science is hard and often fails. That science is for people who are curious and for whom every partial success will bring so much pleasure that they will overcome all the failures that will naturally come.

“There are a lot of very smart people who tried to do science but gave up. Many of us fail and failure is disheartening. But when you occasionally succeed, you overcome previous failures and can move on. And I was lucky enough that each enthusiasm always lasted a long time, usually until the next success, and that's how I overcame the partial failures. In such a constellation, a person sacrifices even the moments when he could be with his family, travel and live, as they say, a normal life," notes Professor Josef Prchal, who, in addition to his work, likes exploring previously unknown places, canoeing on wild water, gardening, skiing and mountain tourism.

Speaking of family, it was perhaps one tragic circumstance that led Josef Prchal on his life's journey.

“My first child died of a genetic disease, spinal muscular atrophy. It caused my first marriage to fall apart years later, but perhaps it was this tragedy that turned me on to science and genetic research.“